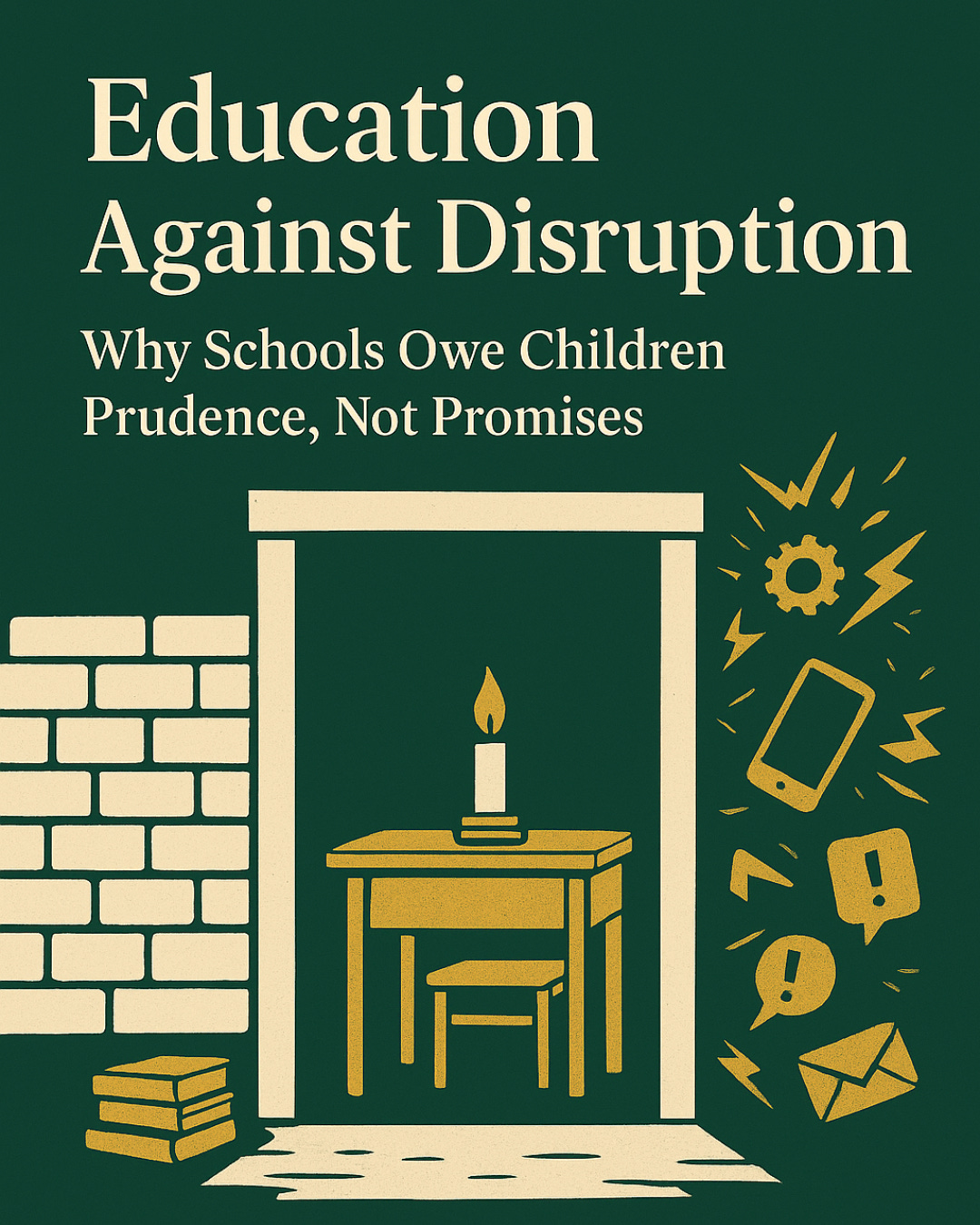

Education Against Disruption

Why Schools Owe Children Prudence, Not Promises

The Gospel of Disruption

“Move Fast and Break Things”

Recent decades have brought economic globalization, political polarization, and accelerating environmental change. But when historians assess education in this era, they may conclude that no force reshaped schooling more completely than digital technology’s culture of disruption:

These reckless slogans weren’t just marketing; they shaped how technology companies built their products. The same ideology produced platforms engineered for addiction, algorithms optimized for engagement over truth, and business models built on surveillance. The results are now visible: increased rates of loneliness, mass dissemination of misinformation, and erosion of privacy.

The tech industry’s faith in disruption derives from Clayton Christensen’s theory of “disruptive innovation”. Originally intended as a neutral analysis of market dynamics – the opportunity for small companies with fewer resources to challenge large, established businesses by targeting overlooked segments of the market with simpler, cheaper products – Christensen’s idea metastasized in the hands of the tech industry into a moral imperative, an ideology.

Their “Gospel of Disruption” preaches technology’s supremacy as a vector for societal improvement. Technology, not politics, is the more powerful first mover. To its faithful, disruption is progress, resistance to disruption is backwards, and therefore there is an obligation to disrupt.

Education, with its compulsory attendance, captive audience of children, and massive public budgets, proved irresistible to an industry that saw every institution as a market waiting to be disrupted. And disrupt, they have – with iPads in kindergarten, Chromebooks in every backpack, and gamified learning platforms that mimic social media’s engagement tactics. The industry packaged disruption as “innovation”, exploiting schools’ fear that failure to adopt meant failing the future.

But their unexamined assumption – that what disrupts is inherently superior to what it replaces – rests on shaky ground. Attention spans are declining, reading comprehension is faltering, test scores are falling, and anxiety is rising. If EdTech was meant to accelerate learning, why has it worsened outcomes?

Perhaps it’s time for schools to adopt a different posture. Perhaps schools have an obligation to cut against this ideology. Perhaps schools should provide and protect the conditions that we know students thrive in.

The Pattern of Unforeseen Harm

What We Learn When We Break Things

We make a mess. Some disruptions lead to long-term benefits, but others reveal their costs slowly, and the vulnerable pay first. Where disruptive innovations race to market without careful concern for consequence, disarray tends to follow.

In order to better understand the risks of disruptive innovation, it may be helpful to examine past decisions that had profound unintended consequences. While we look back on these technologies with certainty today, it’s important to remember that they were cutting edge and broadly embraced when first introduced. The harms vary wildly in scale, from environmental degradation to permanent disability, but the pattern of failure is consistent: technologies adopted rapidly based on immediate benefits, with long-term costs that emerged slowly, fell disproportionately on the vulnerable, and by the time harms became clear, damage had already been done – damage that was often irreversible for those affected, even when the technology itself could be withdrawn or regulated.

Case 1: Asbestos

The widespread use of asbestos as a building material began in the late 19th century. It presented a competitive advantage, combining exceptional heat resistance, fireproofing, tensile strength, durability, and low cost in one material, which no competitor at the time could match: the perfect disruptive innovation. By the middle of the next century, asbestos was found in three to five thousand different products ranging from electrical equipment to bowling balls.

But the early warning signs about its health consequences were ignored. The first documented case of an asbestos-related death was reported in 1906. The industry succeeded in concealing its own knowledge of the hazards by as early as 1940. Later that decade, the evidence for a link between asbestos and lung cancer was mounting, and by 1960, it was specifically tied to mesothelioma.

Despite known risks, the use of asbestos in manufacturing continued to grow inexorably until the mid 1970s. Millions of children were exposed because schools, institutions charged with protecting children, became sites of prolonged exposure to the known carcinogen. And asbestos-related disease continues to be a problem today. The World Health Organization estimates that “exposure to asbestos causes more than 200,000 deaths globally every year.”

The abatement of asbestos and its consequences continues. It’s expensive and it’s incomplete.

Case 2: Leaded Gasoline

In 1921, Thomas Midgley Jr. told his boss at General Motors that he’d discovered a way of reducing “knocking” in car engines. Midgley added countless substances to gasoline in an effort to solve the problem.

“The most compelling option was actually ethanol. But from the perspective of GM … ethanol wasn’t an option. It couldn’t be patented and GM couldn’t control its production. And oil companies like Du Pont “hated it,” … perceiving it to be a threat to their control of the internal combustion engine.” (Smithsonian Magazine)

Instead, GM endorsed the other substance that Midgley found to work, the one that didn’t threaten their control of the industry, the one they knew to be poisonous: tetraethyl lead.

Leaded gasoline hit the market in 1923 and evidence of lead poisoning began to emerge the very next year. As we know, heavy metals tend to accumulate in the environment: a “comparison of street dirt between 1924 and 1934 found a 50 percent increase in lead levels.” But it wasn’t until 1986 that the United States finally banned lead as an additive for gasoline. In the interim, an estimated 5,000 Americans died of lead-induced heart disease annually. But the effects of lead poisoning weren’t just cardiovascular; lead also damages cognitive function.

Children, because of their physical immaturity, are most vulnerable to neurological injuries. “Chronic lead exposure resulted in a measurable drop in IQ scores during the leaded gas era” – permanent cognitive damage that no amount of intervention could reverse once the harm was done. By the time we understood the full scope of the problem, an entire generation had already been affected.

It took so long to ban leaded gasoline because of resistance from the industry, the economic cost of doing so, and infrastructure dependence on the product.

The Common Thread

These weren’t accidents. They were failures of prudence – failures to act on evidence that already existed. Immediate benefits obscured delayed harms, optimism bias and commercial interests overrode caution, vulnerable populations bore the greatest costs, and once scaled, these decisions proved difficult to reverse and the consequences often persisted. Instead of waiting for proof of harm, regulators began requiring proof of safety before widespread deployment. The Precautionary Principle emerged from exactly these kinds of failures.

The severity of harm varied; asbestos and lead proved catastrophic, while other technologies may cause subtler damage. But the process of failure was identical: commercial interests overriding caution, vulnerable populations bearing costs, and delayed effects protecting institutions from accountability.

The question for education is whether we’ll apply this principle to protect children’s cognitive development, or whether we’ll wait for more evidence to accumulate while another generation grows up in an experiment we didn’t design to understand.

The Precautionary Principle

When Uncertainty Demands Restraint

The acceleration of disruptive innovation in the 20th century led to an explosion of unintended consequences. While new technologies were developed to solve real problems, some created unanticipated negative externalities that imposed harms on people and the environment, putting their net utility into question.

“The emergence of increasingly unpredictable, uncertain, and unquantifiable but possibly catastrophic risks such as those associated with Genetically Modified Organisms, climate change, etc., has confronted societies with the need to develop a[n] … anticipatory model to protect humans and the environment against uncertain risks of human action: the Precautionary Principle.” (UNESCO)

The Precautionary Principle maintains that when an activity raises threats of harm to the environment or human health, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully established. In many domains, this isn’t a radical idea; it’s already policy in contexts where vulnerability is recognized. Health Canada, the Food and Drug Administration in the U.S., and other national regulatory bodies require that all new drugs be tested before they’re released to market. In both the U.S. and Canada, pesticides are subject to an additional tenfold margin of safety for infants and children.

The basic logic of the Precautionary Principle is that, where harm is persistent or irreversible and victims can’t consent, the burden of proof shifts to those introducing the risk. So what role should it play in school environments?

Our Fiduciary Responsibility

Schools as Trustees, Not Consumers

The Precautionary Principle is particularly urgent when applied to children and technology in schools. Children cannot consent to being subjects in an uncontrolled experiment, yet their school attendance is compulsory. This creates a heightened obligation to protect developing minds during critical periods of brain development, when experiences shape neural architecture in ways that can be lasting. Moreover, the effects of early technology exposure often don’t appear for years: longitudinal studies show that screen time in early childhood predicts cognitive and behavioural problems that emerge only later in development. By the time these effects become visible, the damage has already been done.

This creates a special relationship – one that is not contractual, but fiduciary. Schools, administrators, and teachers have an obligation to represent the best interests of those with whom we’ve been entrusted: children. As fiduciaries, we can’t claim, “I didn’t know,” when harm occurs; we must exercise heightened diligence in advance.

The current reality is one in which schools adopt technologies on vendor promises, not on evidence. But the inverse should be the case: vendors should be required to prove safety and pedagogical efficacy. Schools, teachers, and parents shouldn’t have to prove harm after its effects have fallen on the shoulders of vulnerable children.

In the classroom, students assume their teachers have their best interests in mind. They trust that the most responsible party in the room is the adult. They believe that the technology they’ve been asked to use doesn’t pose a risk to their wellbeing or development because a fiduciary has selected it. Teachers need to ask themselves: are those beliefs and assumptions well-founded?

What Fiduciary Responsibility Requires

In order to get this right, our mindsets must shift. Schools need to be understood as unique environments where the conditions for learning should be optimized according to the best evidence we have. We must hold them to higher standards than we see in the broader marketplace, just as hospitals have higher standards for hygiene and cleanliness than most public spaces.

Several principles can guide our thinking in this way:

Enact a moratorium on unproven technologies, and only adopt new tools when independent evidence of safety and pedagogical efficacy exists.

Institute a waiting period. When a new educational technology appears on the market, wait 12 to 24 months before introducing it to the classroom. This allows time for preliminary research to take place, for harms to surface, and for alternatives to emerge.

Shift the burden of proof in procurement. Before adopting new tools, vendors must provide:

Evidence of pedagogical benefit (not just engagement metrics)

Disclosure of energy/environmental costs (especially important for AI)

Data on cognitive effects

Plans for harm mitigation

Establish sunset clauses. All educational technology pilots should expire automatically after an agreed-upon term, and will require evidence-based renewal to continue.

Normalize child-specific impact assessments. Before adoption, schools must assess:

Cognitive development effects

Attention and executive function impacts

Equity implications

Privacy and data concerns

Environmental costs

Maintain protected analog spaces. Preserve low-tech alternatives even when digital tools are adopted, in physical spaces and in the curriculum. By doing so, we afford optionality and opportunities for comparison.

Schools should not be venues of market experimentation. We can’t afford to risk unforeseen harms in institutions whose downstream effects implicate the future of our societies. If there’s a place where the Precautionary Principle is essential, it’s in our schools.

The Debt We Owe the Children We Compel

The pattern is clear: disruption promises immediate gains, delivers delayed harms, and leaves the vulnerable to pay the price. We’ve seen it with asbestos, with leaded gas, and now we’re watching it unfold with technology in schools.

We need an alternative to Facebook’s “move fast and break things.” We need schools that move carefully and protect what we know children need: sustained attention, protected time for deep work, environments free from commercial manipulation. Not because technology is inherently bad, but because children are compelled to attend, can’t consent to experiments, and develop in critical periods where harms may be irreversible.

The fiduciary duty demands action. Vendors must prove safety and efficacy before adoption, not after damage is done. Schools must establish waiting periods, sunset clauses, and impact assessments. Our students deserve stability, not disruption. It’s what we owe the children we compel to trust us.

This isn’t caution born of fear. It’s responsibility born of history. We’ve broken things before. We know what happens when we move fast with children’s lives. It’s time schools chose prudence over promises. And if schools lead with this courage, policymakers may finally follow.

If this piece resonated with you, please consider sharing it with the educators, parents, and administrators in your circle. The question of what schools owe their students in an era characterized by disruption deserves wider attention.

For those who find value in this work and want to support its continuation, paid subscriptions make it possible for me to continue researching, writing, and advocating for the conditions children need to thrive. Thank you for your support.

This is excellent, Andrew! Those that have been pushing technology in schools have written books using "Disruptive Innovation" in their titles. The NTIA is holding a listening session tomorrow (12/10) https://www.ntia.gov/events-and-meetings/kids-excessive-screen-time-listening-session. You should consider speaking. As an SLP, I plan to speak about how excessive screen time impacts students and their learning.

Great piece! I really appreciate the comparison to healthcare. Of note, healthcare systems have Quality and Safety oversight mechanisms, both internal and with external regulators. Healthcare providers at an individual level document everything and are supposed to have transparent workflows. This has been made possible by a long-term shift in culture, in which healthcare professionals (especially those with lots of degrees!) welcome and participate in this oversight as a vital component of competent care, rather than fight it as an offense to their professional expertise.

I think in K-12, the tangible paper-based curriculum had organically allowed for parents to be the quality and safety oversight mechanism. But with a digital curriculum, that is no longer the case.